The Life of a duck

Something ought be said, first and foremost, about the concept of the retrospective conceit; without which preface, in this context, all that follows– text and music alike– would come across as naught but the greatest heap of nonsense (against the likelihood of which judgement I confess I cannot insure, even with the explanation to follow).

The retrospective conceit (for a work of “art”), though somewhat arbitrarily appended to a fundamentally abstract entity, is nevertheless a handy conceptual device to employ when attempting to suggest narrative clarity to an audience which, in the present age, implicitly expects as much in all its wonted consumptions. And yet, it is perhaps not so arbitrary after all, for on certain occasions– not unlike this very one– it can be very difficult to fashion such a conceit, certainly more so than if it could simply be drawn from thin air (or so I would like to imagine). It might be, then, that the formation of the retrospective conceit is akin to finding a name for an idea; a name which, though it defines, yet has fundamentally nothing within it save circumstantial attraction to the named– but what’s in a name, if not that attraction?

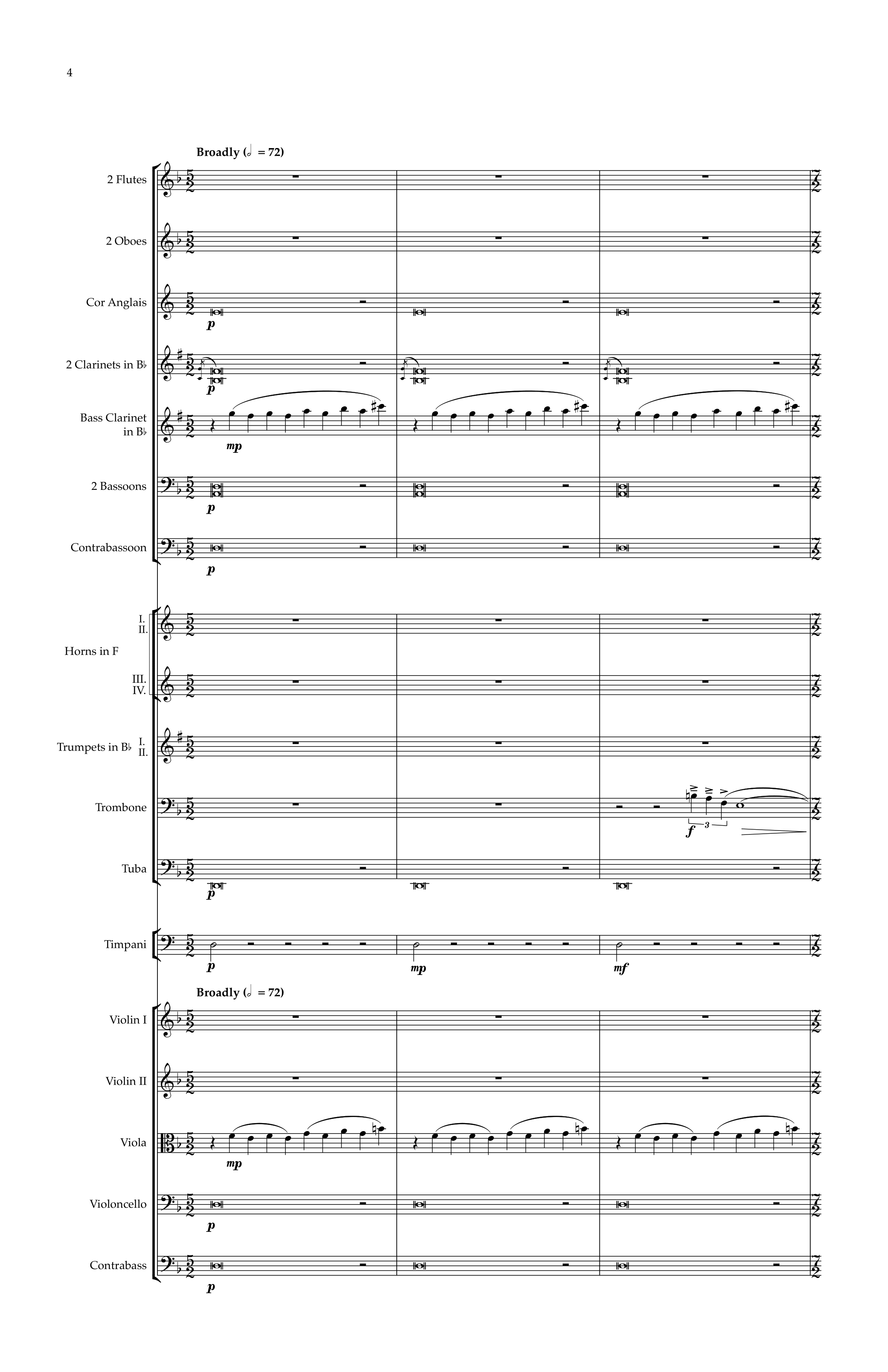

It is in precisely the respect just elucidated that the musical composition entitled “The Life of a Duck” bears its peculiar moniker. Its composer, without doubt, had no sugarplum waterfowl dabbling around his head during its creation; nor had he, at any rate, the slightest inkling concerning what the piece, even upon its completion, might be about. Wherefore, turning again to face his subconscious, whence the work itself had originated, he scoured it for the schema most likely to resonate both internally and externally with the apparent content of the musical work– returning the stare, he at last found, was a pair of duck eyes.

Thus, the reader and listener will, I lament to report, find no fowl chronicle of meager woe and soaring triumph sketched by the musical composition in question– for neither was that the composer’s intent, prospectively or retrospectively; nor is it what, if anything, he achieved. Think more that if you should hereafter in your travels chance to encounter a duck in your or its wild; and, having had this experience– having been tormented by ideas of conceits and names and the subconscious, and worse still by the music– reflect on that duck; if you should, I say, under those fortuitous circumstances of a duck encounter, hold that duck in a little higher a regard, or better yet, should ponder it later after your encounter, and become a little more interested in ducks thereby– then, by all means, this whole ordeal was worth it.